Skanderbeg

| Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Portrait of Skanderbeg in the Uffizi, Florence. | |

| Reign | 1443-1468 |

| Predecessor | Gjon Kastrioti |

| Spouse | Donika Komneni |

| House | Kastrioti |

| Father | Gjon Kastrioti |

| Mother | Vojsava Tripalda |

| Born | 6 May 1405 Dibër, Albania |

| Died | 17 January 1468 (aged 62) Lezhë, Albania |

| Burial | Saint Nicholas church of Lezhë, Albania |

Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg (16 May 1405 – 17 January 1468; Albanian: Gjergj Kastrioti Skënderbeu, widely known as Skanderbeg, Turkish İskender Bey, meaning "Lord Alexander" or "Leader Alexander"), or Iskander Beg, was a prominent historical figure in the history of Albania and of the Albanian people. Known as the Dragon of Albania,[1] he is the national hero of the Albanians and initially through the work of his main biographer, Marin Barleti, is remembered for his struggle against the Ottoman Empire, whose armies he successfully ousted from his native land for more than two decades.[2]

Early life and family

Born in the Stelushi Castle, in the Mat District of Dibër County, Albania, Skanderbeg was a descendant of the Kastrioti family.

According to Gibbon,[3] Skanderbeg's father was Gjon Kastrioti, lord of Middle Albania, which included Mat, Krujë, Mirditë and Dibër. His mother was Vojsava[4] a princess from the Tripalda family,[5][6] (who came from the Polog valley, north-western part of present-day Republic of Macedonia), or from the old noble Muzaka (Musachi) family.[7][8] Gjon Kastrioti was among those who opposed[9] the early incursion of Ottoman Bayezid I, however his resistance was ineffectual. The Sultan, having accepted his submissions, obliged him to pay tribute and to ensure the fidelity of local rulers, George Kastrioti and his three brothers: Reposh, Kostandin, and Stanisha, were taken by the Sultan to his court as hostages.[4]

Service in the Ottoman Army

Skanderbeg went through the Devşirme system, which conscripted Christian boys and converted them to Islam to be trained as officers.[10] After his conversion[11] he attended the military school in Edirne and led many battles for the Ottoman Empire to victory. For his military victories, he received the title Arnavutlu İskender Bey, (Albanian: Skënderbe shqiptari, English: Lord Alexander, the Albanian) comparing Kastrioti's military brilliance to that of Alexander the Great.

He was distinguished as one of the best officers in several Ottoman campaigns both in Asia Minor and in Europe, and the Sultan appointed him General. He even fought against the Greeks, Serbs and Hungarians, and some sources say that he used to maintain secret links with Ragusa, Venice, Ladislaus V of Hungary, and Alfonso I of Naples.[12] Sultan Murat II gave him the title Vali which made him General Governor. Skanderbeg came to lead a cavalry unit of 5,000 men with which he subdued a large part of Anatolia.[13]

Albanian resistance under Skanderbeg

The rise

|

|||||

On November 28, 1443, Skanderbeg saw his opportunity to rebel during a battle against the Hungarians led by John Hunyadi in Niš as part of the Crusade of Varna. He switched sides along with 300 other Albanians serving in the Ottoman army. After a long trek to Albania he eventually captured Krujë by forging a letter[9] from the Sultan to the Governor of Krujë, which granted him control of the territory. After capturing the castle, Skanderbeg[3] abjured Islam and proclaimed himself the avenger of his family and country. He raised a flag with the double-headed eagle, his family's own motif and the historical representation of Christian Empires, most notably the Holy Roman Empire and the Byzantine Empire. This flag and symbol are still in use today by Albania (seeAlbanian flag) and various other states and authorities of the Balkans, Eastern Europe andCentral Europe.

Skanderbeg allied with George Arianiti [14](born Gjergj Arianit Komneni, who shared a distant relation with the Byzantine Komnenos dynasty from one of his great grandmothers)[7] and married his daughter Andronike (born Marina Donika Arianiti).[15]

Following the capture of Krujë, Skanderbeg managed to bring together all the Albanian princes in the town of Lezhë[16] (see League of Lezhë, 1444). Gibbon[3] reports that the"Albanians, a martial race, were unanimous to live and die with their hereditary prince" and that"in the assembly of the states of Epirus, Skanderbeg was elected general of the Turkish war and each of the allies engaged to furnish his respective proportion of men and money". With this support, Skanderbeg built fortresses and organized a mobile defense force that forced the Ottomans to disperse their troops, leaving them vulnerable to the hit-and-run tactics of the Albanians.[17] Skanderbeg fought a guerrilla war against the opposing armies by using the mountainous terrain to his advantage. Skanderbeg commanded an army of about 18,000 soldiers[18], but only had absolute control over 3,500 men from his own dominions and had to convince his colleagues that his policies and tactics were the right ones.[7]

In the summer of 1444, in the field of Torvioll, the united Albanian armies under Skanderbeg faced the Ottomans under direct command of the Turkish general Ali Pasha, with an army composed of 25,000[19] to 40,000[20] men. Skanderbeg had under his command 7,000 infantry and 8,000 cavalry. 3,000 cavalry were hidden behind the enemy lines in a nearby forest under the command of John Musachi (Albanian: Gjon Muzaka) . At the given signal, they descended, encircling the Turks and giving Skanderbeg a much needed victory. About 8,000[7] to 22,000[20] Turks were killed and 2,000 were captured. His victory echoed across Europe because this was one of the few times that an Ottoman army was defeated in a set piece battle on European soil. In the coming years, Skanderbeg defeated the Turks two more times, once in 1445 in Moker (Dibra), and once more in 1447 in Oranik (Dibra).

In 1447, Skanderbeg was also involved in a conflict with the Republic of Venice, (Albanian-Venetian War (1447–1448)) due to the capture of a castle in Northern Albania (Danja) by the Republic of Saint-Marc. During the conflict, Venice invited the Ottomans to attack Skanderbeg simultaneously from the east, provoking a double-sided conflict for the Albanians. Skanderbeg, who had besieged a few castles that were possessed by Venice in Albania, was forced to fight an Ottoman Army under the conduct of Mustafa Pasha. In 1448 he won the battle against Mustafa Pasha in Dibër; some days later he won in Shkodra another battle against a Venetian Army led by Andrea Venerio. At the same time he besieged the towns of Durrës and Lezhë which were under Venetian rule.[21] This forced the Venice to offer a peace treaty to Skanderbeg[21] The peace treaty was signed between Skanderbeg and Venice on 4 October 1448 and soon after Skanderbeg left to join John Hunyadi in Kosovo.

Although it is commonly believed that Skanderbeg took part in the Second Battle of Kosovo in 1448, he actually never arrived. He and his army were en route to reinforce the mainly Hungarian army of John Hunyadi, but Hunyadi did not wait for Skanderbeg[22] while he was delayed by Brankovic.[2] About the time of the battle, Murad II also launched an invasion of Albania in order to keep Skanderbeg busy. Although Hunyadi was defeated in the campaign, Hungary successfully resisted and defeated the Ottoman campaigns during Hunyadi's lifetime.[12]

In 1449 an Ottoman army led by Sultan Murad II laid siege to the castle of Sfetigrad. The Albanian garrison in the castle resisted the frontal assaults of the Ottoman Army, while Skanderbeg harassed the besieging forces with the remaining Albanian army under his personal command. In late summer 1449 due to lack of potable water[23] the Albanian garrison surrendered the castle with the condition of a safe passage through the Ottoman besieging forces, a condition which was accepted and respected by the sultan.[24]

In June 1450, an Ottoman army numbering approximately 100,000 men led again by Sultan Murad II himself laid siege to Krujë.[25] Following a practise of scorched earth (thus denying the Ottomans the use of necessary local resources), Skanderbeg left a protective garrison of 1,500 men under one of his most trusted lieutenants, Vrana Konti (also known as Kont Urani), while with the remainder of the army he harassed the Ottoman camps around Krujë and attacked the supply caravans of the sultan's army. Three major Ottoman direct assaults on the city walls were repelled by the garrison, causing great losses to the besieging forces. Ottoman attempts at finding and cutting the water sources failed and the same happened with a sapped tunnel, which crumbled suddenly. An offer of 300,000 aspra (Turkish money) and a graduation to the Turkish army made to commander of the garrisonVrana Konti was disdainfully rejected by him.[26] By September the Ottoman camp was in disarray as morale sank and disease ran rampant. Murad II acknowledged the castle of Krujë would not fall by strength of arms and in October 1450, he lifted the siege and made his way to Edirne, leaving behind losses amounting to 20,000 dead.[27] Soon thereafter in the winter of 1450–1451, Murad died in Edirne and was succeeded by his son Mehmed II.

The consolidation

Although achieving a great success at resisting the Sultan himself, the country couldn't reap the harvest and famine was widespread. Following Skanderbeg's requests king Alfons of Naples helped him in this situation and the two parties signed in 1451 the Treaty of Gaeta, which was later used as an excuse for Skanderbeg in his Italian campaign. Also, in 1451 Skanderbeg married the daughter of Gjergj Arianiti, one of the most influential Albanian noblemen, strengthening the ties between them.

For the next five years Albania was allowed some respite as the new sultan set out to conquer the last vestiges of the Byzantine Empire, though a couple of minor battles took place in the meanwhile at the Albanian frontiers, all of which were won by the Albanian Army. Christianity in the Balkans was dealt an almost fatal blow when the Byzantine Empire was extinguished after the Fall of Constantinople in 1453. The first real test between the armies of the new sultan and Skanderbeg came in 1455 during the Siege of Berat that would end in the most disastrous defeat Skanderbeg would suffer. Skanderbeg besieged the town's castle for months, causing the demoralized Turkish officer in charge of the castle to promise his surrender. At that point Skanderbeg relaxed the grip, split his forces and left the siege location. He left behind one of his generals, Muzakë Topiaand half of his cavalry at the bank of the river Osum to finalize the surrender. It would be a costly error.

The Ottomans saw this moment as an opportunity for attack. They sent a large cavalry force from Anatolia to Berat as reinforcements. The Albanian forces had become overconfident and lulled into a false sense of security. The Ottomans caught the Albanian cavalry by surprise while they were resting in the shores of the Osum. Almost all the 5,000 Albanian cavalry laying siege to Berat were killed. Most of the forces belonged to Gjergj Arianiti and this defeat minimized his role as the greatest supporter of Skanderbeg.

This defeat affected somewhat the attitude of other Albanian noblemen. One of them Moisi Arianit Golemi defected to the Turks and in 1456 returned to Albania as a commander of a Turkish army of 15,000 strong, but was defeated by Skanderbeg in a swift battle. Later that year a remorseful Moisi Arianit Golemi returned to Albania asking for Skanderbeg's forgiveness, and once acquitted, remained loyal up to his death in 1464.

In the beginning of 1457, another nobleman, Hamza Kastrioti, Skanderbeg's own nephew, defected to Turks. In the summer of 1457 an Ottoman army numbering approximately 70,000 men[12] invaded Albania with the hope of destroying Albanian resistance once and for all; this army was led by Isa beg Evrenoz, the only commander to have defeated Skanderbeg's forces in the battle of Berat, and Hamza Kastrioti, Skanderbeg’s nephew. After wreaking much damage to the countryside[12] the Ottoman army set up camp at the Ujebardha field (literally translated as "White water"), halfway between Lezhë and Krujë. After having avoided the enemy for months, calmly creating the impression to the Turks and European neighbours that he was defeated, on September 2, Skanderbeg attacked the Ottomans in their encampments and defeated them. This was one of the most important and glorious victories of Skanderbeg over the Ottomans, which led to a five-year peace treaty with Sultan Mehmed II. Hamza was captured and sent to detention in Naples.

The last years

On 17 April 1461 Skanderbeg signed a three-year armistice with the sultan. This allowed him to launch in late summer 1461 a successful campaign[16] against the Angevin noblemen and their allies (Francesco Piccinino) who sought to destabilize King Ferdinand I of Naples. For his services[28] he gained the title of Duke of San Pietro in the Kingdom of Naples. After securing the Neapolitan kingdom, a crucial ally in his struggle, he returned home, informed of the Ottoman movements within the borders. There were three Ottoman armies approaching: the first one, under the command of Sinan Bey, was defeated at Mokra (near Dibër); the second one, under the command of Hasan Bey, was defeated in the Battle of Ohër where the Turkish commander was captured; and the third one was defeated in the region of Shkupi.[29] This forced the sultan to agree to a ten-year armistice which was signed in April 1463.[21][30] Inspired by the Crusade declared by Pius II and hearing of the Pope and crusaders army presence in Ancona, in the beginning of August 1464 Skanderbeg's forces attacked and defeated Sheremet Bey's forces near Ohrid lake.[21] But when the pope died and the crusade dispersed, Skanderbeg's forces remained alone against sultan. In April 1465 at the First Battle of Vajkal Skanderbeg fought and defeated Ballaban Badera, an Albanian Ottoman general. However, during an ambush in the same battle, Ballaban managed to capture some important Albanian noblemens,[31] including Moisi Arianit Golemi, a cavalry commander;Vladan Giurica, the chief army quartermaster; Muzaka of Angelina, a nephew of Skanderbeg, and 18 officers. These men were sent immediately to Constantinople (Istanbul) where they were skinned alive for fifteen days and later cut to the pieces and thrown to the dogs.[21][31] Skanderbeg's pleas to have these men back, by either ransom or prisoner exchange, failed.

Later that same year two other Ottoman armies appeared on the borders. The commander of one of the Ottoman armies was Ballaban Badera, who together Jakup Bey, the commander of the second army, planned a double-flank movement: firstly, Skanderbeg attacked Ballaban's forces at the Second Battle of Vajkal where the Turks were defeated, but this time all the Turkish prisoners were slain in an act of revenge for the previous execution of Albanian captains;[21] the other Turkish army, under the command of Jakup Bey, was also defeated some days later in Kashari field near Tirana.[21]

In 1466 Sultan Mehmed II personally led an army into Albania and laid siege to Krujë as his father had attempted sixteen years earlier. The town was defended by a garrison of 4,400 men, led by Prince Tanush Topia. After several months of siege, destruction and killings all over the country, Mehmed II (Fatih-The Conqueror), like Murad II, saw that seizing Krujë was impossible for him to accomplish by force of arms. Subsequently, he left the siege to return to Constantinople (Istanbul). However, he left a force of 40,000 men under Ballaban Pasha to maintain the siege, even building a castle in central Albania, which he named Il-basan (the modern Elbasan), to support the siege. Durrës would be the next target of the sultan, in order to be used as a strong base opposite the Italian coast.[32] Skanderbeg spent the following winter in Italy, unsuccessfully seeking aid in Rome and Naples. However, on his return he allied with Lekë Dukagjini, and together on 19 April 1467 they first attacked and defeated, in Kërraba region, the Turkish reinforcements commanded by Jonima, the brother of Ballaban Pasha, while Jonima himself was killed.[21] Four days later, on 23 April 1467, they attacked the Ottoman forces and laying siege to Kruja. The Second Siege of Kruja was eventually broken, resulting in the death of Ballaban Pasha by an Albanian arquebusier[7] named Gjergj Aleksi.[21]

After these events, Skanderbeg's forces besieged Elbasan, but lacked artillery and sufficient numbers to capture it by direct assaults.[21] The destruction of Ballaban Pasha's army and the siege of Elbasan, forced Mehmed II to march again in summer 1467 against Albania. He energetically pursued the attacks against the Albanian strongholds, while sending detachments to raid the Venetian possessions and to keep them isolated. The Ottomans failed again to take Kruja and subjugate the country, but the degree of destruction was immense.

During the annual Ottoman incursions, Albanians suffered a great number of casualties, especially to the civilian population and the economy of the country was in ruin. The above problems, the loss of many Albanian noblemen and the new alliance with Lekë Dukagjini caused Skanderbeg to call together in January 1468 all the remaining Albanian nobleman to a conference in the Venetian stronghold of Lezhë to discuss the new war strategy and restructuring what remained from the League of Lezhë. During that period Skanderbeg fell ill to malaria and soon died on 17 January 1468. After his death none of the remaining Albanian nobleman had the authority and the stature to make organized resistance to the Turkish forces. Kruja was besieged again in 1474 and in 1478 was finally captured by the Ottoman forces. In 1479 an Ottoman army, headed by the Sultan himself, besieged and captured Shkodra[33] and this marked the end of organised Albanian resistance.[21]

Skanderbeg's diplomacy

Relations with the Papal States

Skanderbeg's military successes evoked a great deal of interest and admiration from the Papal States, Venice, and Naples who were threatened by the growing Ottoman power. As an active defender of the Christian cause in the Balkans, Skanderbeg was also closely involved with the politics of four popes, including Pope Pius II, who hailed him as the Christian Gideon.[28]

Skanderbeg's relations with the Papal States were intensified under Pope Calixtus III. But Skanderbeg's military undertakings involved considerable expense, which the contribution ofAlfons V of Aragon was not sufficient to defray. Following the Ottoman invasion in 1457 Skanderbeg requested help from Pope Calixtus III who was in financial difficulties. The pope could do no more than send Skanderbeg a single galley and a modest sum of money, promising more ships and larger amounts of money in the future. But Ragusa refused bluntly to release the funds which had been collected in Dalmatia for the crusade and, which according to the pope, were to have been distributed in equal parts to Hungary, Bosnia and Albania. The Ragusans even entered into negotiations with Mehmed. At the end of December 1457, Pope Calixtus III threatened Ragusa with an interdict and when this failed he repeated it in February 1458. After the victory of Ujëbardhaon December 1457, Pope Calixtus III appointed Skanderbeg as captain general of the Curia in the war against the Turks, but once again Venice destroyed the prospects for a favorable turn in Albania by raising new claims. As the captain of the Curia, Skanderbeg appointed as a lieutenant in his native land, the duke of Levkas (Santa Maura), Leonard III Tocco, formerly the prince of Arta and "despot of the Rhomaeans" a figure virtually unknown except in Southern Epirus[34]

Profoundly shaken by the fall of Constantinople in 1453, Pope Pius II tried to organize a new crusade against the Ottoman Turks, and to that end he did his best to come to Skanderbeg's aid, as his predecessors Pope Nicholas V andPope Calixtus III had done before him. The latter named him captain general of the Holy See. They gave him the titleAthleta Christi, or Champion of Christ. Pope Pius II planned a crusade in which he would assemble 20,000 soldiers in Taranto and another 20,000 would have been gathered by Skanderbeg. They would have been summoned in Durazzo under Skanderbeg's leadership and would have organized the central front against the Ottomans. This plan forced Skanderbeg to break his 10 year peace treaty with the Ottomans signed in 1463, by attacking the Turkish forces near Ohrid. But Pope Pius II died at the crucial moment when the crusading armies were gathering and preparing to march in Ancona, in August 1464 and Skanderbeg was again left alone facing the Ottomans.[21]

The papacy was generous with praise and encouragement, but its financial subsidies were limited. It is possible tha curia only provided to Skanderbeg 20,000 ducats in all, which could have paid the wages of twenty men over the whole period of conflict.[35] During the winter of 1466–7 when the situation was critical Skanderbeg spent several weeks in Rome trying to persuade Pope Paul II to give him money. At one point, he was unable to pay for his hotel bill, and he commented bitterly that he should be fighting against the Church rather than the Turks.[21] Only when Skanderbeg left for Naples did Pope Paul II give him 2,300 ducats. The court of Naples, whose policy in the Balkans hinged on Skanderbeg's resistance, was more generous with money, armaments and supplies. Ragusa and Venice helped when it was their interest to do so. But it is probably better to say that Skanderbeg financed and equipped his troops largely from local resources, richly supplemented by Turkish booty.[35]

Relations with the Republic of Venice

In the beginning of the Albanian insurrection, Venice was supportive of Skanderbeg, considering his forces to be a buffer between them and the Ottoman Empire. Accordingly, the League of Lezhë was held in Venetic territory with the approval of Venice. The later affirmation of Skanderbeg and his rise as a strong force in their borders was seen as a menace to the interest of the republic and this led to a worsening of relations, leading to the case of Danja which triggered the Albanian-Venetic War of 1447–1448. Not withstanding the forces of Skanderbeg they sought by every means to overthrow, or bring about the death of, this "formidable one" [36], even offering a life pension of 100 ducats annually for the person who could do so.[21] In that period they also requested the help of the sultan[37] and when Skanderbeg defeated the Venetic army at Shkodra and the Turkish army at Oronik, they requested armistice and a peace treaty with "buoni amici e vicini"(good friends and neighbours) was signed on 4 October 1448. Venice agreed to pay Skanderbeg 1,400 ducats for keeping Danja and its environs but would cede to Skanderbeg the territory of Buzëgjarpri at the mouth of the river Drin, and also Skanderbeg would enjoy the privilege of buying, tax-free, 200 horse-loads of salt annually from the Venetic customs.[21]

During the First Siege of Krujë, the Venetic merchants furnished the besieging Ottoman army. The attack by Skanderbeg on their caravans raised tension between the parties, but the case was resolved with the help of the bail of Durrës which would not allow any Venetic merchants to furnish the Ottoman army.[21]

The senate of Venice further resented Skanderbeg's alliance with the Kingdom of Naples, an old enemy of the republic. Frequently they delayed their tributes to Skanderbeg and this was long a matter of dispute between the parties, with Skanderbeg threatening and Venice conceding.[21]

The position of the republic changed when they entered in their first war with the Turks (1463–1479). During this period the republic saw Skanderbeg as an invaluable ally, and in 1464 the peace treaty was renewed and this time other conditions were added: the right of asylum in Venice; an article precising that any Venetian treaty with the Turks would include a guarantee of Albanian independence; and allowing the presence of two Venetian ships in the Adriatic waters around Lezhë.[21][30]

After the death of Skanderbeg, with the request of Skanderbeg's wife, a number of Venetian soldiers were added to the Albanian garrison of Kruja, while she went to take refuge to the Kingdom of Naples together with her 11 year old son Gjon Kastrioti and in this way, Venice was the de facto controller of what was once Skanderbeg's territory.[21] The eventual defeat of Venice and of what remained of their Albanian allies at the Siege of Shkodra in 1479, marked the end of the organised Albanian resistance.

Relations with the Kingdom of Naples

According to some scholars, Skanderbeg and King Alfons kept secret contact when Skanderbeg wassuba at Kruja around 1438. After his ascendance in 1443 they become part of Skanderbeg's diplomacy. The intensification began in 1447 when Skanderbeg got into conflict with Venice. King Alfons I was the main rival of Venice in the Adriatic and his dreams for an empire were always opposed by Venice.

In 1448 Alfonso V of Aragon suffered a rebellion caused by certain barons in the rural areas of his kingdom in southern Italy. He needed reliable troops to deal with the uprising, so he called upon Skanderbeg for assistance. Skanderbeg responded to Alfonso's request for aid by sending to Italy a detachment of Albanian troops commanded by General Demetrios Reres. These Albanians were successful in quickly suppressing the rebellion and restoring order. King Alfonso rewarded Demetrios Reres for his service to Naples by appointing him Governor of Calabria. Two years later, in 1450, another detachment of Albanian troops was sent to garrison Sicily against a rebellion and invasion. This time the troops were led by Giorgio and Basilio Reres, the sons of Demetrios.

In 1451 Albania was in ruin after sultan Murad II was successfully defeatedat Kruja and now it was Skanderbeg's turn to ask for help from King Alfonso. He sent his emissaries to Naples, and after some negotiations, Skanderbeg's representatives, Stephan the Bishop of Kruja and the Dominican Nichola de Berguzzi, signed on 26 March 1451 the Treaty of Gaeta. The treaty was signed not only in the name of Skanderbeg but also "... e de soi parenti, baruni in Albania, de la parte altra" (..... his relatives, barons in Albania, of the other part).

According to the Treaty, Skanderbeg recognized King Alfonso's sovereignty over his lands, in exchange for the help that King Alfonso would give to him in his war against the Ottomans. Skanderbeg even promised to put the lands he and his relatives would eventually conquer from the Ottomans under King Alfonso' sovereignty. King Alfonso pledged to respect the old privileges of Kruja and Albanian territories and to pay Skanderbeg an annual 1,500 ducats, while Skanderbeg pledged to make hisfealty to King Alfonso only after the full expulsion of the Ottomans from the country, a condition never reached in Skanderbeg's lifetime. This fact (the oath never took place) expressively stated in the agreement has raised debate among scholars: was Skanderbeg to be called a vasal of King Alfonso or not? Some maintain that although it looked like a typical vasal treaty, since this treaty was a conditional agreement and the condition was not fulfilled, then Skanderbeg was not even de jure a vasal of Aragon. What is generally accepted is that Skanderbeg de facto had full soverainity over his territories, while Naples archives have registered payments and supplies sent to Skanderbeg, they do not mention any kind of payment or tribute by Skanderbeg, except for various Turkish war prisoners and banners sent by him as a gift of King Alfonso.[21]

At the same time Alfonso V signed different treaties with other Albanian noblemen, including Golem Arianit Komneni[38] and also the Despot of Morea Demeter Paleologue[39] These movements of Alfonso showed that he indeed was thinking about a crusade from Albania and Morea, a crusade which never took place.[21] Following this treaty in the end of May 1451, a small detachment of 100 Catalan soldiers, headed by Bernard Vaquer, was established at the castle of Kruja. In May 1452 another Catalan nobleman, Ramon d’Ortafà, came to Kruja with the title of viceroy. In 1453 Skanderbeg paid a secret visit to Naples and the Vatican, probably discussing the new conditions after the fall of Constantinople and the planning of a new crusade which Alfonso would have presented to the Pope Nicholas V in a meeting of 1453–1454.[40]

In November 1453 Skanderbeg informed King Alfonso that he had conquered some territories and a castle and Alfonso replied some days later that soon Ramon d’Ortafà would have returned to continue the war against the Ottomans (now more than ever) and also promised more troops and supplies. In the beginning of 1454 Skanderbeg and the Venetians[41] informed King Alfonso and the Pope about a possible Ottoman invasion and asked for help. The Pope sent 3,000 ducats while Alfonso sent 500 infantry and a certain sum of money,[42] along with a message directed to Skanderbeg.[43]

In June 1454 Ramon d’Ortafà returned after a long absence to Kruja, this time with the title of viceroy of Albania, Greece and Slavonia with a personal letter to Skanderbeg as the Captain general of the armed forces in Albania.[44] Along with Ramon d’Ortafà, King Alfonso V also sent to Albania the clerics Fra Lorenzo da Palerino and Fra Giovanni dell’Aquila with a tabby flag with an embroided white cross as a symbol of the Crusade which was about to begin.[45] Even though this crusade never begun, the Neapolitan troops were used in the siege of Berat where they were almost entirely annihilated and there were never replaced.

On 27 July 1458, King Alfons V the greatest supporter of Skanderbeg died at Naples while Skanderbeg sent three emissaries, Tanush Topia, Vladan Givrici and Angjelin Muzaka, to his son King Ferdinand. According to Marinescu the death of King Alfonso marked the end of the Aragonese dream of a Mediterranean Empire and also the hope for a new crusade in which Skanderbeg was assigned a leading role.[46] The relationship of Skanderbeg with the Kingdom of Naples continued even after Alfonso V's death. The situation changed; the natural son and heir of Alfonso V Ferdinand I of Naples was not as able as his father and now it was Skanderbeg's turn to help King Ferdinand to regain and maintain his kingdom.

In 1460 King Ferdinand had serious problems with another uprising ofAngevins and asked for help from Skanderbeg. This invitation worriedKing Ferdinand's opponents, while Malatesta declared that if King Ferrante of Naples received Skanderbeg, Malatesta would go to the Turks.[47] Ferdinand's main rival Giovanni Antonio Orsini, Prince of Taranto in a correspondence with Skanderbeg tried to dissuade him from this enterprise and even offered him an alliance. This did not affect Skanderbeg and in the beginning of 1461 Skanderbeg dispatched a company of 500 cavalry under his nephew, Gjok Stres Balsha. When the situation became critical, Skanderbeg made a three year armistice with the Ottomans and in late August 1461 landed himself in Pugliawith an expedition of 1,000 cavalry and 2,000 infantry.[21] At Barletta and Trani, he managed to defeat the Italian and Angevin forces of Giovanni Antonio Orsini, Prince of Taranto and only after he secured King Ferdinand's throne, did Skanderbeg returned to Albania.

King Ferdinand was very grateful with Skanderbeg for this intervention and not only gave to him and his descendants the castle of Trani, properties of Mount Saint Angel and Saint John Rotondo, but also continued to support Skanderbeg with money and supplies.[48] Skanderbeg paid another visit to Naples after he visited Rome in the winter of 1466–67 asking in vain for help.[49] King Ferdinand's gratitude toward Skanderbeg continued even after his death. In a letter dated to 24 February 1468, he expressively stated that "Skanderbeg was like a father to us" and "We regret this (Skanderbeg's) death not less than the death of King Alfonso", offering protection for Skanderbeg's widow and his son. It is relevant to the fact that the majority of Albanian leaders after the death of Skanderbeg found refuge in the Kingdom of Naples and this was also the case for the common peoples trying to escape from the Ottomans, which formedArbëresh colonies in that area.

After death

The Albanian resistance went on after the death of Skanderbeg for an additional ten years under the leadership of Dukagjini, though with only moderate success and no great victories. In 1478, the fourth siege of Krujë finally proved successful for the Ottomans. Demoralized and severely weakened by hunger and lack of supplies from the year-long siege, the defenders surrendered to Mehmed, who had promised them to leave unharmed in exchange. As the Albanians were walking away with their families, however, the Ottomans reneged on this promise, killing the men and enslaving the women and children.[32]

In 1479 the Ottoman forces captured the Venetian-controlled Shkodër after a fifteen-month siege.[50] Shkodër was the last Albanian castle to fall to the Ottomans and Venetians evacuated Durrës in 1501. Albanian resistance continued sporadically until 1912 when Albania was no longer part of the Ottoman Empire.

The union[1] which Skanderbeg had maintained in Albania did not survive him. Without Skanderbeg at their lead, their allegiances faltered and splintered until they were forced into submission. The defeats triggered a great Albanian exodus[50] to southern Italy, especially to the kingdom of Naples, as well as to Sicily, Greece, Romania, and Egypt. Albania remained a part of the Ottoman Empire until 1912.

Effects on the Ottoman expansion

The Ottoman Empire's expansion ground to a halt during the time that Skanderbeg and his Albanian forces resisted. He has been credited with being the main reason for delaying Ottoman expansion into Western Europe, giving the Italian city-states time to better prepare for the Ottoman arrival [7][51]. While the Albanian resistance certainly played a vital role in this, it was one piece of numerous events that played out in the mid-15th century. Much credit must also go to the successful resistance mounted by Vlad III Dracula in Wallachia and Stephen III the Great of Moldavia, who dealt the Ottomans their worst defeat at Vaslui, among many others, as well as the defeats inflicted upon the Ottomans by Hunyadi and his major Hungarian forces.[52] Stephen III the great and Hunyadi having also achieved the title of Athleti Cristi, Defenders of the Christian faith along with Skanderbeg. The particularity of Skanderbeg was the maintaining of such an important and difficult resistance for a long period of time (25 years) against the strongest power of the 15th century's world, by possessing very limited economical and human resources. His leading, political, diplomatical and military abilities was the main factor for the small Albanian principate to achieve such a success.

Descendants

Skanderbeg’s family, the Kastrioti Skanderbeg,[3] were invested with a Neapolitan dukedom after the Turkish pressure became too strong. They obtained a feudal domain, the Duchy of San Pietro in Galatina and County of Soleto (Lecce, Italy).[53] John, Scanderbeg’s son, married Irene Palaeologus, last descendent of the Byzantine imperial family, the Palaeologus. Thus, the Castriota Scanderbeg today represent the only descendants left of the last imperial family of Byzantium.[54]

Two lines of the Castriota Scanderbeg family live onwards in southern Italy, one of which descends from Pardo Castriota Skanderbeg and the other from Achille Castriota Skanderbeg, both being natural sons of Duke Ferrante, son of John and Scanderbeg’s nephiew. They are part of the Italian nobility and members of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta with the highest rank of nobility.[55]

The only legitimate daughter of Duke Ferrante, Irina Castriota Skanderbeg, born from Andreana Acquaviva d'Aragona fromNardò dukes, inherited the paternal estate, bringing the Duchy of Galatina and County of Soleto into theSanseverino family after her marriage with princePietrantonio Sanseverino (1508–1559). They had a son, Nicolò Bernardino Sanseverino(1541–1606), but the legitimate Castrioti name was forever lost with Irina Castriota.

Name

His names have been spelled in a number of ways: George, Gjergj, Giorgi, Giorgia, Giorgio, Castriota, Kastrioti, Capriotti, Castrioti,[9] Castriot,[28] Kastriot, Skanderbeg, Skenderbeg, Scanderbeg, Skënderbeg, Skenderbeu, Scander-Begh, Skënderbej or Iskander Bey.

The name, Skanderbeg has the following explanation: The name which can also be written "Skenderbeu" is the Albanian way of writing the Turkish name Iskender (derived fromAlexander) and the Turkish Bey (Lord or prince). The last name Kastrioti refers to a toponym in northern Albania called Kastriot in Dibra, where Skanderbeg was born. His name was Gjergj Kastrioti and "Skander Bey" was not part of his name, "Skender" was given by the Sultan and he later also gave him the "Bey" title as he was awarded by the Turkish Sultan, meaning Lord Alexander, comparing Skanderbeg's military skill to that of Alexander the Great's. Thus his name was Gjerg Kastrioti and his title was "Lord Alexander".

Seal of Skanderbeg

A seal ascribed to Skanderbeg has been kept in Denmark since it was discovered in 1634. It was bought by the National Museum in 1839. The seal is made of brass, is 6 cm in length and weighs 280 g. The inscription (laterally reversed) is in Greek and reads

ΒΑΣΙΛΕΥΣ.ΑΛΕΞΑΝΔΡΟΣ.ΕΛΕΩ.ΘΥ. ΑΥΤ.ΡΩΜ.ΟΜΕΓ. ΑΥΘ.ΤΟΥΡ.ΑΛΒ. ΣΕΡΒΙ.ΒΟΥΛΓΑΡΙ.

Most of the words are abbreviated, but an English translation might be: King Alexander, by the grace of God, Emperor of the Romans, the great ruler of the Turks, Albanians, Serbs, [and] Bulgarians.

If this seal is authentic, it indicates that George Kastrioti declared himself king, using the name Skender in its Greek form. (Greek or Latin were the customary languages for royal inscriptions in the Middle Ages.) The titles might exaggerate his actual power, but this was often the case for Medieval rulers(especially Serbian ones who needed to assert their legitimacy in the Balkans after the 5th century invasions). Skanderbeg is apparently seen as a successor of theByzantine emperors, as shown by the title and the double-eagled crest, during this period a symbol of Byzantine power. After the fall of Constantinople in 1453 AD, such claims were also made by the Russian Czars. In fact Scanderbeg would have been most likely the successor as Voltaire has suggested but the Byzantines preferred the fall of their empire rather than being commanded by an Epirotan Despotate.

Legacy

The "Dragon of Albania" Skanderbeg, is also credited with the greatest body count. He is said to have slain three thousand Turks with his own hand during his campaigns. Among stories told about him was that he never slept more than five hours at night and could cut two men asunder with a single stroke of his scimitar, cut through iron helmets, kill a wild boar with a single stroke and cleave the head off a buffalo with another.[56]

As part of his internal policy programs, Skanderbeg issued many edicts, like census of the population and tax collection, during his reign based on Roman and Byzantine law.[57]

When the Ottomans found the grave of Skanderbeg in Saint Nicholas, a church in Lezhë, they opened it and made amulets of his bones, believing that these would confer bravery on the wearer.[3]

Skanderbeg today is the national hero of Albania. Many museums and monuments, such as theSkanderbeg Museum next to the castle in Krujë, have been raised in his honor around Albania and in predominantly Albanian-populated Kosovo. Skanderbeg's struggle against the Ottoman Empire became highly significant to the Albanian people, as it strengthened their solidarity, made them more conscious of their national identity, and served later as a great source of inspiration in their struggle for national unity, freedom, and independence.

James Wolfe, commander of the British forces at Quebec, spoke of Skanderbeg as a commander who "excels all the officers, ancient and modern, in the conduct of a small defensive army".[58] On October 27, 2005, the United States Congress issued a resolution "honoring the 600th anniversary of the birth of Gjergj Kastrioti (Scanderbeg), statesman, diplomat, and military genius, for his role in saving Western Europe from Ottoman occupation."[59][60]

Skanderbeg is depicted on the obverses of the Albanian 1000 lekë banknote of 1992–1996, and of the 5000 lekë banknote issued since 1996.[61]

Skanderbeg in literature

Skanderbeg gathered quite a posthumous reputation in Western Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries. With much of the Balkans under Ottoman rule and with the Turks at the gates of Vienna in 1683, nothing could have captivated readers in the West more than an action-packed tale of heroic Christian resistance to the "Moslem hordes".

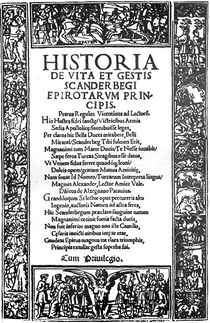

Books on the Albanian prince began to appear in Western Europe in the early 16th century. One of the earliest of these histories to have circulated in Western Europe about the heroic deeds of Skanderbeg was the Historia de vita et gestis Scanderbegi, Epirotarum Principis (Rome ca. 1508–1510), published a mere four decades after Skanderbeg's death. ThisHistory of the life and deeds of Scanderbeg, Prince of the Epirotes was written by the Albanian historian Marinus Barletius Scodrensis, known in Albanian as Marin Barleti,[2] who after experiencing the Turkish occupation of his native Shkodër at firsthand, settled in Padua where he became rector of the parish church of St. Stephan. Barleti dedicates his work to Donferrante Kastrioti,[16] Skanderbeg's grandchild, and to posterity. The book was first published in Latin.

In the 16th and 17th centuries Barleti's book was translated into a number of foreign language versions: inGerman by Johann Pincianus (1533), in Italian by Pietro Rocca (1554, 1560), in Portuguese by Francisco D'Andrade (1567), in Polish by Ciprian Bazylik (1569), in French by Jaques De Lavardin, Seigneur du Plessis-Bourrot (French: Histoire de Georges Castriot Surnomé Scanderbeg, Roy d'Albanie, 1576), and in Spanish byJuan Ochoa de la Salde (1582). The English version was a translation from the French one of De Lavardin and made by one Zachary Jones Gentleman. It was published at the end of the 16th century under the title, Historie of George Castriot, surnamed Scanderbeg, King of Albinie; containing his Famous Actes, his Noble Deedes of Armes and Memorable Victories against the Turkes for the Faith of Christ. Gibbon was not the first one who noticed that Barleti is sometimes inaccurate in favour of his hero;[62] for example, Barleti claims that the Sultan was killed by disease under the walls of Kruje.[63]

Kastrioti's biography was also written by Franciscus Blancus, a Catholic bishop born in Albania. His book "Georgius Castriotus, Epirensis vulgo Scanderbegh, Epirotarum Princeps Fortissimus" was published in Latin in 1636.[64]

Voltaire starts his chapter "The Taking of Constantinople" with the phrase

| “ | Had the Greek Emperors acted like Scanderbeg, the empire of the East might still have been preserved.[65] | ” |

Skanderbeg is the protagonist of three 18th-century British tragedies, William Havard's Scanderbeg, A Tragedy (1733), George Lillo's The Christian Hero (1735), and Thomas Whincop'sScanderbeg, Or, Love and Liberty(1747).[66]

A number of poets and composers have also drawn inspiration from his military career. The French 16th century poetRonsard wrote a poem about him, as did the 19th century Americanpoet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.[67] For Gibbon, "John Huniades and Scanderbeg... are both entitled to our notice, since their occupation of the Ottomanarms delayed the ruin of theGreek empire."

In 1855, Camille Paganel wrote Histoire de Scanderbeg, inspired by the Crimean War.[6]

In the lengthy poetic tale Childe Harold's Pilgrimage (1812–1819), which Byron had begun writing while in Albania, Scanderbeg and his warrior nation are described in the following terms:

| “ | Land of Albania! where Iskander rose, Theme of the young, and beacon of the wise, And he his namesake, whose oft-baffled foes Shrunk from his deeds of chivalrous emprize: Land of Albania! let me bend mine eyes On thee, thou rugged nurse of savage men! The cross descends, thy minarets arise, And the pale crescent sparkles in the glen, Through many a cypress grove within each city's ken." Canto II, XXXVIII. "Fierce are Albania's children, yet they lack not virtues, were those virtues more mature. Where is the foe that ever saw their back? Who can so well the toil of war endure? Their native fastnesses not more secure Than they in doubtful time of troublous need: Their wrath how deadly! but their friendship sure, When Gratitude or Valour bids them bleed Unshaken rushing on where'er their chief may lead. | ” |

Canto II, LXV.George Castriot, surnamed Scanderbeg, King of Albania.[68]

Ludvig Holberg, a Danish writer and philosopher, claimed that Skanderbeg is one of the greatest generals in history.[69]Sir William Temple considered Skanderbeg to be one of the seven greatest chiefs without a crown, along withBelisarius, Flavius Aetius, John Hunyadi, Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba, Alexander Farnese, and William the Silent.[70]

Skanderbeg in popular culture

Many stories regarding Skanderbeg are popular among Albanians. In those he is depicted as a very wise and strong man. For e.g. in one occasion Ballaban Pasha sent to Skanderbeg a gift of four Arabian horses along with a splendid equipment to Skanderbeg honouring him as a commander, while Skanderbeg response to him was a gift composed of a crook and knar, letting Ballaban know that would have been more honorable to him to have been a simple shepherd in his village than to betray his own country. For Albanian peoples Skanderbeg would make miracles with his sword. It was supposed that it could take three man to lift his sword and he could split rocks or perforate mountains with it. In another popular story it is told during negotiations for peace the Sultan Mehmed II, having heard of Skanderbeg sword requested it as a favor from Skanderbeg. Skanderbeg agreed and sent his sword as a gift to the sultan. Skanderbeg's man hearing the news were worried. They asked Skanderbeg about their fears that he handed over his legendary sword, but Skanderbeg laughed and responded that he handed over his sword but not his arm.[71]

Skanderbeg in music

The Italian baroque composer Antonio Vivaldi composed an opera entitled Scanderbeg (first performed 1718). Another opera entitled Scanderbeg was composed by 18th century French composer François Francœur (first performed 1763).[72]

Skanderbeg in film

The Great Warrior Skanderbeg is a 1953 Albanian-Soviet biographical film.[73]

Monuments outside Albania

- The palace in Rome in which Skanderbeg resided in 1466–67 still bears his name. A statue in the city is dedicated to him. The square where the statue resides is named "Piazza Albania".

- In 2006, a statue of Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg was unveiled on the grounds of St. Paul's Albanian Catholic Community inRochester Hills, Michigan, the first Skanderbeg statue in the United States.[74]

- Monuments or statues of Skanderbeg have also been erected in: Skopje, Debar, Pristina, Geneva, Brussels and various locales throughout southern Italy where there is an Arbëreshë community.

List of Skanderbeg's battles and campaigns

Skanderbeg fought in many major battles, most of which ended in victory for the Albanian side.

- Battle of Torvioll (1444)

- Battle of Mokra (1445)

- Battle of Otonetë (1446)

- Albanian–Venetian War (1447–1448)

- Battle of the Drin (1448)

- Battle of Oranik (1448)

- Siege of Sfetigrad (1449)

- Siege of Krujë (1450)

- Battle of Modrica (1452)

- Battle of Pollog (1453)

- Siege of Berat (1455)

- Battle of Oranik (1456)

- Battle of Albulena (1457)

- Skanderbeg's Italian expedition (1461–1462)

- Battle of Mokra (July 1462)

- Battle of Mokra (August 1462)

- Battle of Pollog (1462)

- Battle of Livad (1462)

- Great Macedonian raid (1463)

- Battle of Ochrida (1464)

- Battle of Vajkal (1464)

- Battle of Vajkal (1465)

- Battle of Kashari (1465)

- Siege of Krujë (1466)

- Siege of Krujë (1467)

See also

- Arms of Skanderbeg

- History of Albania

- History of Ottoman Empire

Gallery of statues commemorating Skanderbeg

Statue of Skanderbeg, in Krujë, Albania. |

Statue of Skanderbeg, in Skopje, Republic of Macedonia |

||

Statue of Skanderbeg in Debar, Republic of Macedonia |

Skanderbeg and his men in Krujë, Albania |

References

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Marin Barleti, 1508, Historia de vita et gestis Scanderbegi Epirotarum principis

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Edward Gibbon, 1788, History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Volume 6, Scanderbeg section

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Marin Barleti, 1508, Historia de vita et gestis Scanderbegi Epirotarum principis

- ↑ Noli, Fan Stylian, George Castroiti Scanderbeg (1405–1468), (International Universities Press, 1947), 21.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Camille Paganel, 1855,"Histoire de Scanderbeg, ou Turcs et Chrétiens du XVe siècle"

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Hodgkinson, Harry. Scanderbeg: From Ottoman Captive to Albanian Hero. I. B. Tauris. p. 240. ISBN 978-1-85043-941-7.

- ↑ Fan Noli p. 189, note 33.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 James Emerson Tennent, 1845, The History of Modern Greece, from Its Conquest by the Romans B.C.146, to the Present Time

- ↑ The New Encyclopedia of Islam, Ed. Cyril Glassé, (Rowman & Littlefield, 2008), 129.

- ↑ Rendina, Claudio (2000). La grande enciclopedia di Roma. Rome: Newton Compton. p. 1136. ISBN 88-8289-316-2.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Noli, Fan S.: George Castrioti Scanderbeg, New York, 1947

- ↑ Scanderbeg: A Modern hero by Gennaro Francione, page 15 Ilir

- ↑ Fine, John V. (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. ISBN 0-472-08260-4.

- ↑ Cenni storici sull'Albania(Italian)

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Minna Skafte Jensen, 2006,A Heroic Tale: Edin Barleti's Scanderbeg between orality and literacy

- ↑ Stavrianos, L.S. (2000). The Balkans Since 1453. ISBN 1-85065-551-0.

- ↑ [1] The Albanians by Edwin Jacques, pages 179–180

- ↑ Albania, General Information published by 8 Nëntori Pub. House, page 23

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 George Castriot, Surnamed Scanderbeg, King of Albania by Clement Clark Moore

- ↑ 21.00 21.01 21.02 21.03 21.04 21.05 21.06 21.07 21.08 21.09 21.10 21.11 21.12 21.13 21.14 21.15 21.16 21.17 21.18 21.19 21.20 21.21 Noli 1947

- ↑ [2]Mehmed the Conquerer and His Time by Franz Babinger, page 55

- ↑ Historians have different versions of the facts: with old sources maintaining that a dead dog was found in the castle well, and the garrison refuted to drink the water since it may corrupt their soul (Barletius et al) while the latter historians conjecture that the Ottoman forces found and cut the water sources of the castle

- ↑ Barletius, Noli 1947, etc

- ↑ Logoreci, Anton The Albanians, London, 1977

- ↑ Barletius, Noli 1947,

- ↑ Noli

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Catholic World Encyclopedia VOL. XXIII, Number 134, 1876,Scanderbeg entry

- ↑ Noli 1947 but this last battle is disputed if it happened in that time

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest By John Van Antwerp Fine Edition: reprint, illustrated Published by University of Michigan Press, 1994 ISBN 0-472-08260-4, 9780472082605

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 John Musachi, 1515, Brief Chronicle on the Descendants of our Musachi Dynasty

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Babinger, Franz (1992). Mehmed the Conqueror and His Time. ISBN 0-691-01078-1.

- ↑ Barletius

- ↑ Mehmed the Conqueror and His Time By Franz Babinger, William C. Hickman, Ralph Manheim Translated by Ralph Manheim Edition: 2, reprint, illustrated Published by Princeton University Press, 1992 ISBN 0-691-01078-1, 9780691010786

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 The later Crusades, 1274–1580: from Lyons to Alcazar By Norman Housley Edition: illustrated, reprint Published by Oxford University Press, 1992 ISBN 0-19-822136-3, 9780198221364 (page 91 )

- ↑ Romanin 1853, 4 Marzo 1448, Secreta 17:221

- ↑ Romanin 1853, 25 Maggio 1448, Senati Mar. 62t

- ↑ Archive of Crown of Aragon, reg. 2691, 101 recto –102 verso; Zurita: Anales. IV, 29

- ↑ Archive of Crown of Aragon, reg. 2697, 98–99

- ↑ Marinesco: Alphonse, 69–79; Pall: Skanderbeg,15

- ↑ ASV, Senato Deliberazioni da Mar, V, fl. 8; Ljubic: Listine, X, nr. XXV

- ↑ ASM, Carteggio gen. Sforzasco, ad annum 1454

- ↑ "Magnifico et strenuo viro Georgio Castrioti, dicto Scandabech, gentium armorum magnanimo capitaneo, nobis plurimum dilecto" Noli 1947

- ↑ "Magnifico et strenuo viro Georgio Castrioti, dicto Scandarbech, gentium armorum nostrarum in partibus Albanie generali capitaneo, consiliario fideli nobis dilecto" Noli 1947

- ↑ Jorga: Geschichte des Osmanischen, II, 46; Marinesco: Alphonse, 82

- ↑ Marinesco: Alphonse, 133–134

- ↑ Mehmed the Conqueror and His Time By Franz Babinger, William C. Hickman, Ralph Manheim Translated by Ralph Manheim Edition: 2, reprint, illustrated Published by Princeton University Press, 1992 ISBN 0-691-01078-1, 9780691010786 p 201

- ↑ Although less than his father. Marinesco, Noli etc

- ↑ This time the help of Ferrante consisted in 1000 ducats for his war, 500 ducats for the expends of Skanderbeg's staying in Rome, 200 carts of grain and a loan for more 100 carts of grain.(Noli 1947)

- ↑ 50.0 50.1

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Library of Congress Country Studies.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Library of Congress Country Studies. - ↑ [3] The Story of Turkey by Stanley Lane-Poole, Elias John Wilkinson Gibb, Arthur Gilman, page 135

- ↑ East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000–1500, by Jean W. Sedlar Edition: illustrated Published by University of Washington Press, 1994 ISBN 0-295-97290-4, 9780295972909 Together with Hunyadi and Skanderbeg, Stephen the Great stands out as the only Christian commander on the 15th century able to win major victories over the Turks (page 396)

- ↑ The fall of Constantinople 1453, Cambridge University Press

- ↑ Steven Runciman, 1990, The fall of Costantinople 1453, Cambridge University Press

- ↑ Archivio del Gran Priorato di Napoli e Sicilia del Sovrano Militare Ordine di Malta, Napoli

- ↑ Richard Cohen, 2003, By the Sword: A History of Gladiators, Musketeers, Samurai, Swashbucklers, and Olympic Champions ISBN 978 0812969665 ref; page 151.

- ↑ Barletius, 1508, Historia de vita et gestis Scanderbegi Epirotarum principis

- ↑ Taken fromScanderbeg: From Ottoman Captive to Albanian Hero, page 2, by Harry Hodgkinson who claims his source from Life and Letters of James Wolfe, pages 296–7, by Beckles Wilson, (New York, 1909). [4]

- ↑ COMMITTEE BUSINESS SCHEDULED WEEK OF OCTOBER 24, 2005

- ↑ and Lantos Introduce Congressional Resolution to Honor the 600th Anniversary of the Birth of Gjergj Kastrioti Scanderbeg

- ↑ Bank of Albania. Currency:Banknotes in circulation. – Retrieved on 23 March 2009.

- ↑ see also Chalcondyles, l vii. p. 185, l. viii. p. 229

- ↑ Gibbon, ibid, note 42

- ↑ Georgius Castriotus Epirensis, vulgo Scanderbegh. Per Franciscum Blancum, De Alumnis Collegij de Propaganda Fide Episcopum Sappatensem etc. Venetiis, Typis Marci Ginammi, MDCXXXVI (1636).

- ↑ Voltaire, 1762, Works, Vol 3.

- ↑ Havard, 1733, Scanderbeg, A Tragedy; Lillo, 1735, The Christian Hero; Whincop, 1747, Scanderbeg, Or, Love and Liberty.

- ↑ Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1863,Scanderbeg

- ↑ La personnalité, la pensée, l'oeuvre littéraire. (Didier, Paris 1963) 463 pp

- ↑ Holberg on Scanderbeg by Bjoern Andersen

- ↑ Sir Temple, William (1705). Miscellanea volume II. New York Public Library: J. Tonson. p. 285. http://books.google.com/books?id=w04JAAAAQAAJ&pg=RA1-PA286&dq=Containing+I.+A+survey+of+the+constitutions++skanderbeg&cd=3#v=onepage&q&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

- ↑ Baxhaku, Fatos. "In Debar, at Skanderbeg's birthplace" (in Albanian). Gazeta Shqip. http://www.gazeta-shqip.com/artikull.php?id=63954. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- ↑ The Scanderberg Operas by Vivaldi and Francouer by Del Brebner

- ↑ "Festival de Cannes: The Great Warrior Skanderbeg". festival-cannes.com. http://www.festival-cannes.com/en/archives/ficheFilm/id/3875/year/1954.html. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

- ↑ Delaney, Robert (29 September 2006). "Welcoming Skanderbeg — Cd. Maida, Albanian president unveil statue of Albanian hero". The Michigan Catholic. Archdiocese of Detroit. http://www.aodonline.org/NR/exeres/751B4426-7845-4911-A0CC-F83EB09EC140.htm.

Literature

- Marinus Barletius. Historia de vita et gestis Scanderbegi Epirotarum Principis. Rome: Bernardinus de Vitalibus, 1508–1510. (in Latin) Eng trans: History of the life and deeds of Scanderbeg Prince of the Epirotes. Earliest known published book about Scanderbeg.

- Jacques de Lavardin and Seigneur du Plessis-Bourrot. Histoire de Georges Castriot, Surnommé Scanderbeg, Roy d'Albanie. Franche-ville: pour Jean Arnauld, 1604. (in French) Based on Marin Barleti's book. (Google Books, full access)

- Clement Clarke Moore. George Castriot, Surnamed Scanderbeg, King of Albania. New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1850. (Google Books, full access)

- James Meeker Ludlow. The Captain of the Janizaries. New York: Harper & brothers, 1890. This is a novel. (Google Books, full access. Also on The Internet Archive)

- Alessandro Laporta. La vita di Scanderbeg di Paolo Angelo (Venezia, 1539). Un libro anonimo restituito al suo autore. Congedo, 2004. ISBN 88-8086-571-4, ISBN 978-88-8086-571-1. (in Italian) Reprint from 1539.

- Thomas Whincop. Scanderbeg: Or, Love and Liberty. London: W. Reeve, 1747. This is a play (a tragedy), the first known of several plays to have been written about Scanderbeg. (Google Books, full access)

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Fan Noli. Skenderbeu. Boston, 1916. (in both Albanian and English) This is poem about Scanderbeg, adapted in Albanian and published by Fan Noli. (Google Books, full access)

- Franciscus Blancus. Georgius Castriotus, Epirensis vulgo Scanderbegh, Epirotarum Princeps Fortissimus, published in Latin, Venice, 1636.

Additional sources

- Adapted from Fan S. Noli's biography George Castrioti Scanderbeg

External links

- I Castriota Scanderbeg (Italian)

- Heraldic Source on Scanderbeg

- Benjamin Disraeli, 1833, The Rise of Iskander, (Note this is historical fiction)

- Analysis of literature on Scanderbeg

- Scanderbeg: Warrior-King of Albania — trailer of a documentary

- Military History Timeline of Skanderbeg

- Marinus Barletius: History of George Castriot, surnamed Scanderbeg: Chapter XII

| Preceded by Ballaban Pasha (Ottoman occupation) |

Prince of Kastrioti 28 November 1443 – 2 March 1444 |

Succeeded by Post abolished |

| Preceded by Post created |

Head of League of Lezhë 2 March 1444 – 17 January 1468 |

Succeeded by Lekë Dukagjini |